Mark E. Fischer conceived Plain Wrapper Press Redux as a way of reviving a long-standing interest in and passion for creating books in limited editions – books that honor pre-industrial methods of production and that are capable of stirring the heart by their beauty. As a teenager, Fischer had the opportunity to learn from master printer Gabriel Rummonds at the Plain Wrapper Press (PWP) in Verona, Italy. Fischer’s enchantment with the craft grew as he observed and assisted Rummonds with his press work. By age 14, Fischer had established his own press, the Stamperia Ponte Pietra, which published four limited editions before he turned 19.

Fischer’s career took a different direction, but his friendship with Rummonds continued. Four decades later, in search of an enterprise that engaged his creative impulses, he thought of the legacy of the PWP and began exploring the possibility of creating book editions in the tradition of that work. PWP had ceased operation in 1988. Surveying the current range of publications in the “contemporary book arts” domain, Fischer perceived that, while there is abundant creativity and experimentation, the level of craft in service to the text that PWP exemplified was less in evidence. Fischer took the occasion of Rummonds’ 90th birthday to suggest to him the idea of a “Plain Wrapper Press Redux.” Rummonds was enthusiastic and had recommendations of authors and of book arts specialists who could execute the vision.

For Fischer, that vision embraces limited-edition books like those he first encountered in the 1970’s, with excellent typography and sensitively integrated artwork, all the elements – the texture of the paper, the subtle impression of letterpress, the binding and overall design – conveying a sense of wholeness and rightness that quicken the heart.

I make no claim to clinical detachment insofar as the work of Gabriel Rummonds is concerned. I have the profoundest admiration for the publications of the Plain Wrapper Press.

When a private press offers its products to the public, the private quotient comes to reside in those qualities that set apart the items printed as distinct, identifiable even when shelved with hundreds of other volumes, possessing qualities in text and visual dress so clearly personal that the book bears two names: its own title and the name of the press from whence it came. Thus, the basic question each private press must address is: “What makes your products different from the products of other private presses?”

The Kelmscott-Doves-Ashendene classic heritage offers such inclusive rubrics that perhaps as much as 98% of all Twentieth-century private press work can find shelter in this ample tabernacle. Stylistically and textually repetitive, they inspire the question: “Why was most of this work done?” There are lots of answers: the experience of production, new collectors and resultant new collections, keeping alive for each new decade the concept of the “fine” book, etc. All these answers are proper, but with a few exceptions, the private press in our century just did not fulfill its potential.

I noted in this hurried overview of the private press that there were a few exceptions to the general pattern. Use both hands, ten fingers – you won’t need all ten to count the exceptions. But clearly one of them is the work of Gabriel Rummonds.

Rummonds’s selection of art liberated the texts used. The art in a Plain Wrapper Press book refuses to be dated — thus assuring the viewer of a Plain Wrapper Press book a century from now an almost equal opportunity to come to the pages of text and rejoice in the feast of meaning. The same conclusion can be hoped for in Rummonds’s selection of type, although prediction as to the nature of the visual word of a century from now is less sanguine. Who knows what a century of computer-ugliness will do to the form of letters?

To Morris and his circle we all owe an incredible debt for his insistence upon quality of materials and the articulation of certain canons of book design. Mr. Rummonds, while entirely different in perspective, has paid full dues in these matters.

Up until 1993, my relationship with Plain Wrapper Press publications was one of sheer hedonistic enjoyment. Another side of the story, the production side, first was made known to me in reading the [then] unpublished text of Rummonds’s memoir, Fantasies & Hard Knocks: My Life as a Printer. I was unprepared for this text, having assumed, I guess, that the PWP books just appeared out of the ether of Gabriel Rummonds’s genius. There was genius there and lots of it. But there was also blood, sweat, and tears, and anger, frustration, disappointment, and Job-like trials. With rare exception, the production of a PWP book came at a monumental physical and psychic cost. The search for the right paper, or the delay of months between placing an order and its delivery; the varying needs of different types of paper for dampness; the tedium of spacing letters, etc. – all add up to a chorus of crushing woes seeking to abort almost every project at hand. For some books, the troubles were years in duration.

Surely the highest psalm of praise should go to the man whose attitude could be described as “I’ll get it done when I get all things right,” rather than the stance of “Let’s get it done and over with” of we lesser mortals.

Every bit of Rummonds’s makeup throbs with Theater. It’s part of his blood and breath. Thus, he is a master of exits. The two pieces announcing his exit from printing will remain long in memory. One small card paying respects to the academic rat race will bring wonderful joy whenever it is rediscovered by generations in the future. The other piece – Seven Aspects of Solitude – is one of the most beautiful packages of genuine tragedy I’ve ever encountered. Friends and the supporters of the press remain hopeful that he will once again resume his place in the field of printing. I bet Rummonds could bring off a return that would put his famous exits in the shade!

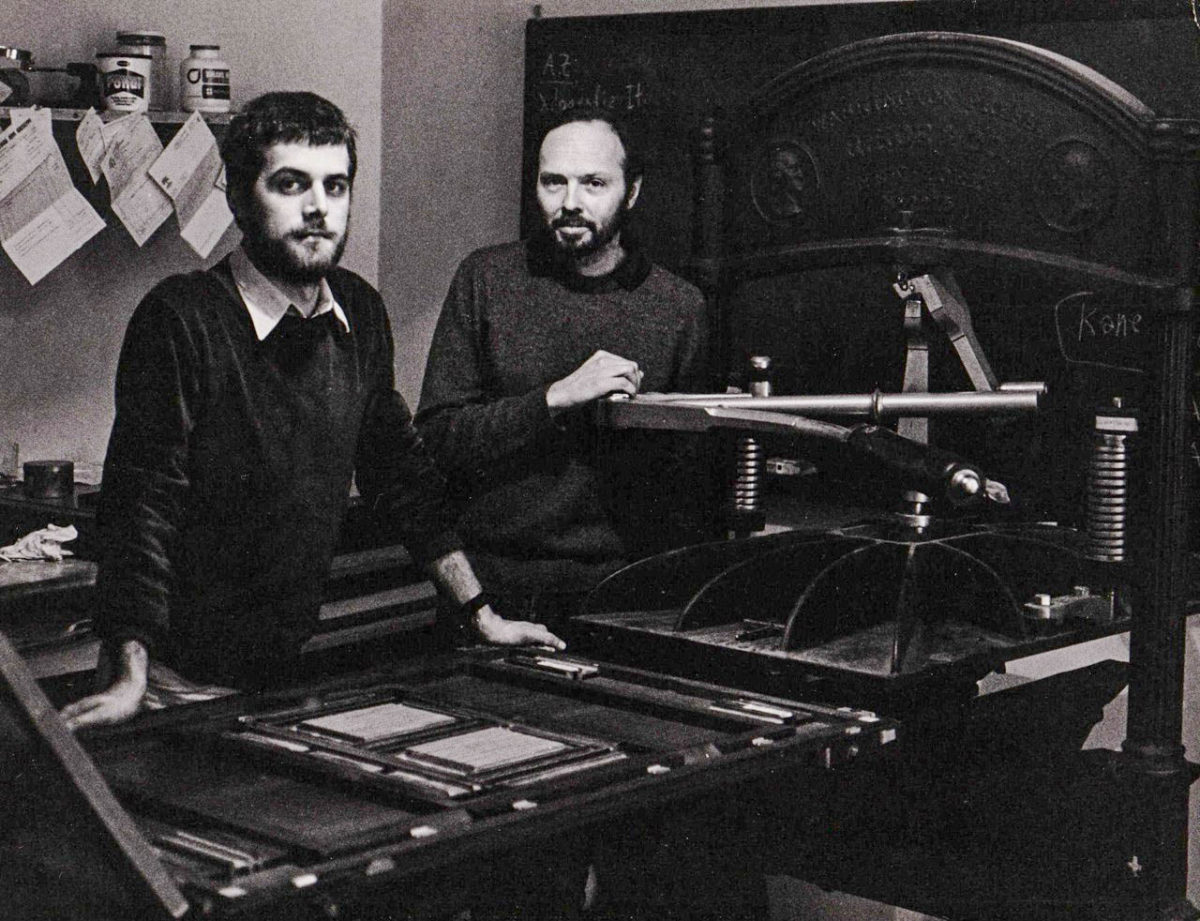

Gabriel Rummonds founded the original Plain Wrapper Press (PWP) in Quito, Ecuador, in 1966. PWP’s first book was a selection of Rummonds’s own poems. The following year in Buenos Aires, Argentina, PWP printed and published a book of Rummonds’s short stories. In 1967, Rummonds moved the PWP to New York City, where he first met the Italian handprinters Giovanni and Martino Mardersteig and he purchased a cast-iron Washington handpress. In 1970, Rummonds moved his publishing venture and printing equipment to Verona, Italy, where he remained until 1982. Alessandro Zanella joined Rummonds at the PWP in 1976, and he became his business partner in 1978.

During this period in Verona, the PWP printed one of the great treasures of Twentieth-century fine-press publishing: Siete Poemas Sajones/Seven Saxon Poems by Jorge Luis Borges with impressions by Arnaldo Pomodoro. Other editions featured texts by Anthony Burgess, Italo Calvino, C.P. Cavafy, John Cheever, Brendan Gill, Dana Gioia, Luigi Santucci, Vittorio Sereni, Jack Spicer, Laure Vernière, and Paul Zweig. Illustrators included Antonio Frasconi, Mirek, Ariel Parkinson, Ruggero Savinio, Roger Selden, Fulvio Testa, and Joe Tilson. In 1982, the PWP moved to Cottondale, Alabama, where it was eventually reborn as Ex Ophidia Press without Zanella’s participation. In 1984, in Verona, Zanella founded Edizioni Ampersand, which continued to print and publish handprinted limited editions until Zanella’s untimely passing in 2014.

The original Plain Wrapper Press editions are in the collections of the following institutions.